Historical Reconstructions

Evensongs - OEM & CREOR

As semi-professional musician, I've been involved in one historical reconstruction, under the production of Alexandra Buckle, and am currently involved in another with the Montreal-based choral collective One Equall Musick of which I'm a founding member. In 2012-2013, One Equall Musick collaborated with McGill's Centre for Research on Religion (CREOR) to present a series of Evensong reconstructions which explore transitional moments in English choral music.

Anna Lewton-Brain, Christopher Hossfeld, and I are finalizing an article on the series, and how it relates to historical performance practices, and historical reconstructions of liturgical life.

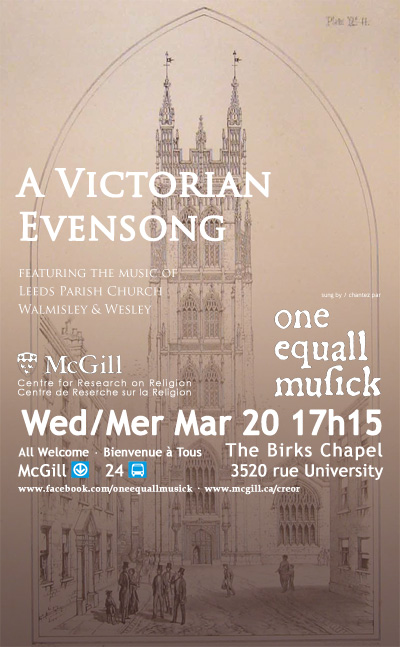

Early Victorian Evensong, 20 March 2013

The third in the series was an early Victorian evensong from Leeds parish church c.1850. Leeds Parish church was an early leader in what would become the Oxford Movement, a liturgically and doctrinally conservative thread within the Victorian established church that aimed to reclaim English medieval ritual life in the face of staunch English evangelicalism. Set at the start of this movement, outside a cathedral context, and in a urban church in an industrial city, this evensong explored the burgeoning of what would become the full drama of Victorian and later Edwardian English church music. The Oxford Movement's neo-gothic and romantic sensibilities meant slowing down tempi, and perhaps a bit more dramatic production to the sound. Once again, we used organ, but also recycled earlier Tudor music, as would become a Victorian fad for recovering the "medieval" and "English Catholic" past.Repertoire List:

- Psalm 104 (Samuel Sebastian Wesley), from The European Psalmist, Tunes by Dr. Woodward, Dr. Dupuis, and S. S. Wesley

- Evening Service in D minor, Thomas Attwood Walmisley

- Cast me not away, Samuel Sebastian Wesley

- Preces and Responses, Thomas Tallis

- Abide with me, William Henry Monk

Early Elizabethan, 6 February 2013

The second in the series did not begin as an Early Elizabethan reconstruction, but rather an Edwardine service from the early 1550s. The interest was in exploring two aspects of mid-Tudor choral music: the transitional nature of Edwardine English settings and anthems, often counterfeited late medieval pieces, and the nature of English Psalmody prior to the adoption of Geneva chant. Though we were able to find adequate service music from the Wanley and Lumley Partbooks, we stumbled on finding psalmody that fit the day - those found in the Wanley book were exactly of the type we needed, except for the texts! We didn't want to sing monodic chant or fauxbourdon, so we ended up shifting our time period slightly after an attempt to set contemporary psalm translations to altered Wanley tunes. Though this was proving an interesting editorial and compositional exercise, it was ultimately too time-consuming. And so we settled on an Evensong as it might have been sung in a large collegiate church or Cathedral in the early 1570s after the publication of Tallis's psalm tunes. Little did we know at the time that David Skimmer was doing much the same with Alamire! The result was a service which combined Wanley / Lumley music, with that of the new Elizabethan settlement. The most fascinating aspect of this reconstruction was the pacing of the psalms. Rather than opt for a moderate tempo, which would mean a full two-verse run through of Tallis's tunes at c.1:30, we opted for a significantly quicker pace, almost 1/2 again faster. The change in the musicality was noticeable. Some audience members noted that after 3 or 4 verses, the chant resembled a mantra of sorts, acquiring a steady flowing rhythm that rolled along without lingering overly on the text. This change in tempo was brought about by the simple question - if someone used to singing monastic chant, rather than Anglican chant, approached Tallis's tunes for the first time, in a context where they had to recite some 60-70 verses during an evensong, would they linger as some English choirs do? The experiment was geared towards trying to work out these practicalities in context. Personally, I found the faster pace added much to the music, making it more lively, and maybe more representative of actuality than overly manicured (and perhaps romanticized) approaches to a Genevan chant. The entire service was acappella, and there was no sermon or homily. While the 1559 service doesn't mention choral anthems, we took the liberty provided by the 1548 injunction allowing anthems in cathedrals to perform at the back of the chapel following the service.

Repetoire List:

- Psalms 32 (1st tune), 33 (8th tune) & 34 (4th Tune), Thomas Tallis, Archbishop Parker’s Psalter

- First Service, Robert Parsons

- Deliver me, Robert Parsons

- Preces and Responses, John Merbecke

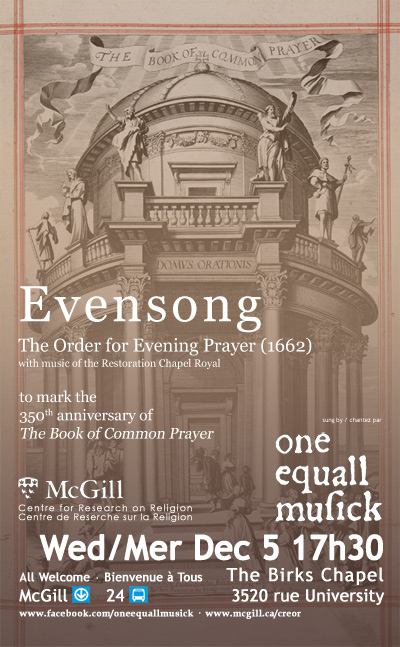

Restoration Chapel Royal Evensong, 5 December 2012

This was reconstruction of a typical evensong from the Chapel Royal in the early to mid-1660s on 5 Dec 2012. The project drew attention to the anniversary of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, but also examine little known composers like Humfrey, Cooke, and Batten, in the generation prior to Henry Purcell. Samuel Pepys, in his diary on 22 Nov. 1663, remarked on hearing the pleasant music set by some of 'Captain Cooke's Boys' in the Chapel Royal - young chorister composers like Humfrey or Blow who found themselves placed at the heart of the musical life of the English court at the end of the seventeenth century.

Repetoire List:

- Psalms 27 (14th and 12th Tunes), 28 (8th and 15th Tunes) & 29 (Imperial), from British Library MS 17784

- Evening Service in E minor, Pelham Humphrey

- Behold, thou hast made my days, Orlando Gibbons

- Preces and Responses, William Smith

- The Lord will come and not be slow, John Milton & Old 107th, The Scottish Psalter (1635)

- Fantasia Number 6, John Jenkins

- Fantazia of foure parts, Orlando Gibbons

Warwick

Richard Beauchamp's Obit, St Mary's Collegiate Church, 10 October 2004

Under the direction of Alexandra Buckle, the Men of St Mary's Collegiate Church Choir performed a reconstructed Obit or funeral commemoration service for Richard Beauchamp, the Beauchamp Chantry Chapel's founder. Richard Beauchamp is buried in the midst of the chapel itself.  The music included works by Soursby among other mid-fifteenth century English composers and period chant.

The music included works by Soursby among other mid-fifteenth century English composers and period chant.